Below, please find part-one of Dr. Harding’s reflections on her recent trip to our Wellness Clinic in Goma.

Of Goma, I can say first that I am sad to leave it, and our friends here. And that it brings to life a Russian saying, “May I never experience all that one can get used to.” The doctors, nurses, and staff at the wellness clinic and programs work every day and night (literally) to provide care for some of the most marginalized people on the planet. The clinic and hospital treat very sick and vulnerable patients, with very limited resources. They care for children and adults who are clearly “ICU-sick” without the machinery, the drugs, or the access to consultation upon which we rely.

They have a frankly excellent anesthesia team who has reportedly never lost a patient on the table- but doesn’t have a functioning anesthesia machine. Dr. Desire performs surgeries there that would involve two or three teams, take seven hours, and cost a year’s salary in the US. He does this with the bare minimum of equipment at his disposal, and does it well. In a rare instance, he brings in a colleague for support. But generally, he is on his own. There is no anesthesia machine, no cautery, one suction for two ORs, and both rooms routinely bake during the afternoon. My watch registered the room temperature at 92 degrees during an abdominal surgery on Monday.

The labor and delivery team deliver 25 plus babies a week- no EFMs, no monitoring at all except for their skills- gloves are precious here, and they run out. One woman, struggling at transition, reached out to grab the nurse’s hand during a contraction. Gritting her teeth and abstracted by pain, she prayed aloud. The nurses stood patiently by, awaiting the next appropriate time to assess her progress. “I’m an orphan,” she said, “my family are all gone. This child will heal me. God bless you.”

I don’t have the words to convey what life is like there for people- it would be presumptuous anyway. I can try to tell you a little about how it felt to be there. It is a youthful city- and in its deeply skewed demographics, it is like much of Africa (young). Every third or fourth building is under construction. And the (literally) breathtaking Lake Kivu is both near and far- regardless of what neighborhood you’re in. Much of the waterfront is private property- you can be a half block away, but you can not see it. I won’t belabor statistics, since that is more or less searchable data- how many displaced (close to one million, we think), how many living below the poverty line (and there is a LOT of room below that line).

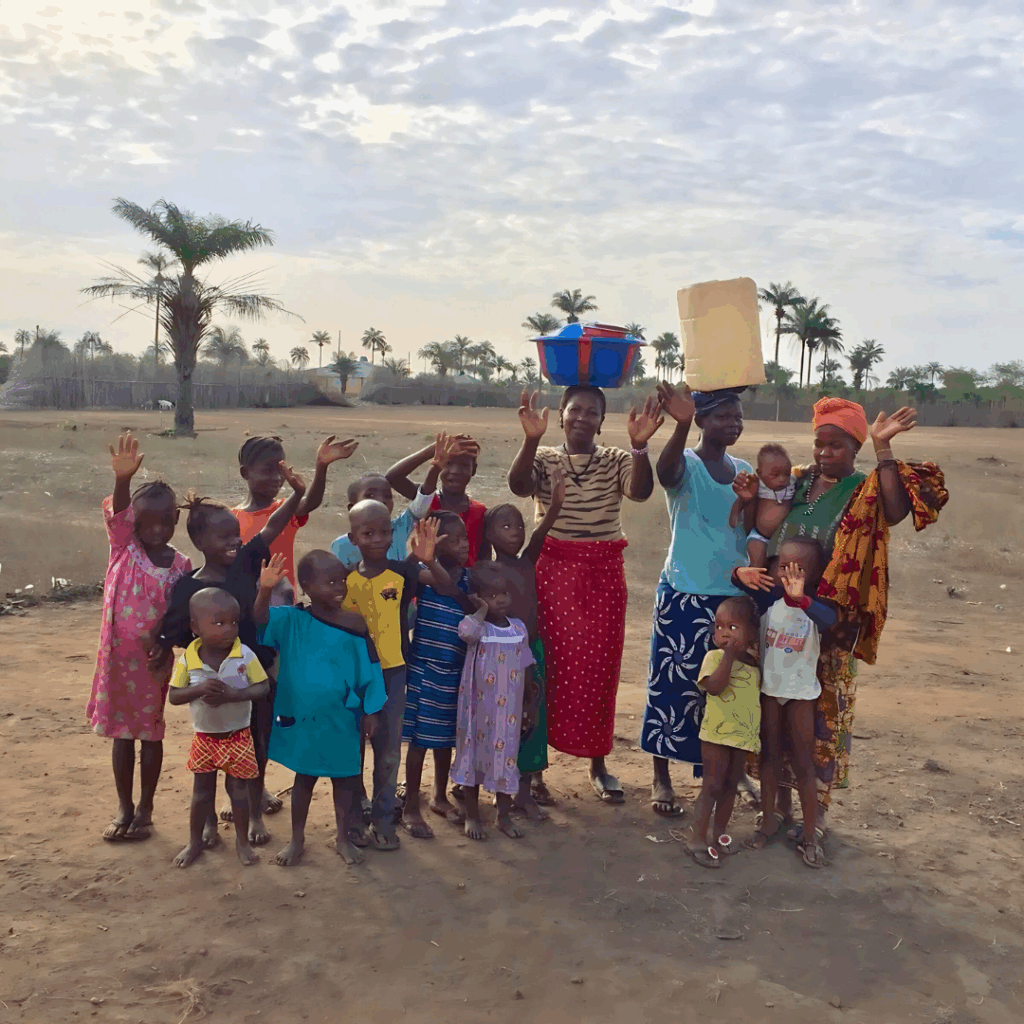

Goma has its own sense of home. And within the home called Goma, there is a little village made up of a clinic, and the families who work and go there for medical care. I wondered, before I met our colleagues at New Hope, why they don’t leave- given the dangers of staying here. Unlike the displaced, many of our colleagues at New Hope could, in theory, leave if they wanted to. Staying carries, at all times, the threat of death. Living here from day to day, as it is with living anywhere, demands that a person cultivate a mental economy- a sense of the energy required to minimize danger and maximize survival over time. People learn to breathe in the diesel dust and volcanic ash, to avoid entanglements with the soldiers, to navigate the curvilinear array of streets, to build a little business selling produce or diesel from a cart, or to find good grazing lits for their goats. In time, the ordinariness of daily life anywhere eclipses the daily challenges. That is, people can get used to anything.

Nevertheless, the threat of violence is always in the air. It settles on everything, like the dust and the exhaust. It sticks to you, like sweat. I asked myself, “How do you come and go from your home and your clinic, from the grocery store, from your mom’s house- at all times aware that soldiers might come gunning for your family, or the volcano might (will) again erupt, or the lake might explode and send jets of gas into the air that push oxygen out of your lungs and suffocate you?” One of our colleagues saw the alarm on my face when the staff were talking about run-ins with soldiers while commuting, and the very significant potential each encounter carries for being shot. He smiled and told me, “We know all the time that something bad might happen, but if we leave, who will see the patients? Also, it is not that easy to find work everywhere, but here there is always work. There are so many in need, many of them have no place else to go for care. We are needed, so we hope that this will keep us safe.”

These colleagues of ours are, in short, heroes. In spite of their struggles just to do the work from day to day, they are all so eager to learn- so welcoming of any opportunity to better understand and excel in the care of human beings. Seeing patients with Drs. Francois, Mugabe, Prince, and Fidel was a transformative learning experience for me. I hope I was able to teach them something, too. Dr. Deluca, Roseline, Angela, Mya Win and I will be working with them on some applicable standard of care protocols going forward, and are looking forward to learning with them again. We will advocate for them in every way we can once we are home. They deserve every effort. The setting in which our Goma team operates is extraordinary.

-Dr. Elizabeth Harding